Tipping Facts and Resources

History of Tipping

One major overlooked component of tipping is its history. Sometime in the mid 1800’s, people picked up the custom in Europe and brought it back to America as an aristocratic custom, to show off or prove their elevated education, class and sophistication. In its early days in practice, tipping spread and was linked to the racial oppression of the post Civil War Reconstruction period.

In the beginning, most poor white Americans deemed tipping inherently condescending and classist. It seemed unreasonable to be expected to pay for food AND also add a tip. Tipping was initially rejected by most Americans, as seemingly un-American. Six states temporarily abolished the practice in 1915. In 1918, Georgia’s legislature deemed tips as “commercial bribes”, or tips for the purpose of influencing service, illegal. Iowa’s initial 1915 decision said that those who accepted a gratuity of any kind — not those who gave the money themselves — could be fined or imprisoned.

So how/why did tipping become a staple of American tradition and practice?

The Constitution was amended after the Civil War, and slavery was ended as an institution, but racism and bigotry would live on in infamy. After slaves were freed from bondage, there were very few jobs in which blacks could be employed. These included jobs such as sharecropping, railroad porters, masons, carpenters, servants, waiters, and barbers. For servants and railroad porters, there was an unfortunate reality; Many white owned business operators still refused to pay blacks for their work. Instead, employers would offer jobs to blacks on the condition that they would work for a $0 wage, plus tips from guests. This essentially amounted to the continuation of slavery, under the guise that some compensation was being afforded to workers. Many hotel, restaurant, and service related industries, quickly began to see the huge benefits in subsidizing a workers pay via guests tipping. This practice became the norm and tipping became a common custom of everyday America. Employers subsidizing workers pay with tips, still persists today. Its evolved into the current tipped minimum wage. There are 15 states that currently still adhere to the $2.13 federal tipped minimum wage.

Unions

There are nearly 12 million people working in American restaurants. That’s more than 2.2 million servers, 1.7 million cooks, 779,000 supervisors, and another 3.2 million people employed in combined food-prep and food- service jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). They’re employed in all types of establishments —fast-food and full-service, institutional cafeterias, catering kitchens, and bars. Yet only 1.3 percent of them are union members—which puts restaurants in a dead heat with the finance industry for the lowest unionization rate of any sector. Labor statistics show that number hasn’t changed much over the last 20 years. This very public push for higher wages and better job conditions didn’t come out of nowhere. It’s part of an ongoing effort that emerged from the Fight For $15 movement, which is backed by the nearly two million-strong Service Employees International Union (SEIU). The movement began in 2012, as a series of one-day strikes held by fast-food workers in New York, Chicago, and then in other cities across the country. Eventually, low-wage earners in airports and universities, home-health aides, and others, joined the cause. Since that time, SEIU claims, 24 million people have received $70 billion in raises. 50 years ago, according to labor experts, unions captured a much larger share of the industry. This can largely be attributed to the simple reasons that dining out was simpler, fewer people did it on a regular basis, and the industry itself was smaller. In 1963, Americans spent less than 30 percent of their food expenditures away from home. Now it’s more than half. Dining out is more prismatic today. To wit: The National Restaurant Association, an industry trade group, tracks a dozen different dining categories. Its members run full-service (family, casual, fine dining), and limited-service (“quick service,” fast casual, cafés, snack bars) establishments. They operate institutional cafeterias, buffets, caterers, bars, and food trucks. First and foremost, SEIU is trying to raise their wages. “The fast-food protests,” as Fight For $15 was once known, were borne of the reality that fast-food employees are increasingly adults with families to feed. Supporting that effort may prove to be a savvy organizing strategy, in part because higher wages reduce turnover, which is a major obstacle for the labor movement. Union economics makes the prospect of organizing the fast-food sector store by store, tens of thousands of times over, a daunting one. Erik Forman, a former Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organizer, points out that starting unions is a job, too, and typically it’s paid by member dues. Practical obstacles make fast food unionization a long shot. But what about finer dining, in some of the country’s most celebrated restaurant cities?

n New York City, for example, it’s entirely possible for a server to make a middle-class living, in a fine-dining establishment, because tips can be a significant income source. But, those above-average earnings challenge labor’s ability to make inroads. There’s a point when the financial rewards outweigh the job’s drawbacks—like poor scheduling or no health insurance. It’s an irony of organizing, that poor working conditions, and the resulting turnover, make it harder to form unions, while decent jobs create a lack of interest.

Copyright Sam Bloch contributing writer for The Counter

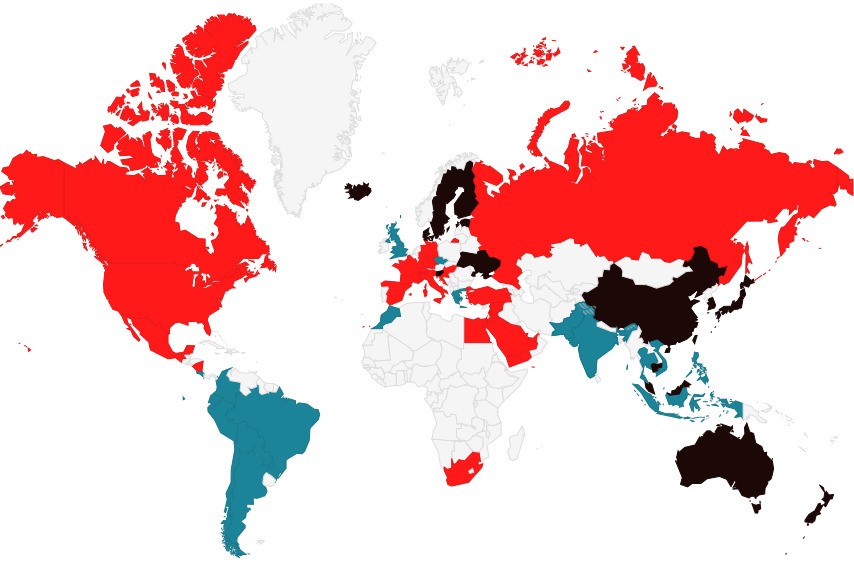

Tipping in other Countries

For those of you whom have had the chance to travel abroad, tipping is not customary in many countries. Countries such as France, China, Japan, French Polynesia, South Korea, Switzerland, Hong Kong, Australia, Belgium, and Denmark, to name a few, have a culture of not tipping. In some countries it is interpreted as impolite, while in others, gratuity is already included in the check. In most of these countries, servers are paid a living wage, provided healthcare, and get paid vacation days. Most servers in these countries do not live off tips. For Americans traveling abroad, Tip Dec is the perfect solution for dining out experiences. If you feel a bit of anxiety or unfamiliarity in not leaving a tip, simply leave a Tip Dec, expressing gratitude and appreciation for the service you received.

Tipping = Subsidizing Employee Pay

Unless you’ve worked in the service industry, more specifically the restaurant industry, then you are probably unaware of the tipped minimum wage. A tipped minimum wage is the Federal Government’s required minimum wage for workers that receive at least $30 per month in tips. In the event that wages and tips do not equal the Federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour during any week, the employer is required to increase cash wages to meet the federal minimum. This tipped minimum wage is a relic of the post Civil War era. During Reconstruction, many employers benefitted from employing workers at $0 wages + tips from guests. This allowed an owner to essentially get free labor, and shift the burden of an employee’s salary on to the consumer. This subsidizing of employee wages is grossly unfair to the employees and consumers alike. This business model puts an undue amount of stress on employees to endure un-welcomed commentary from guests, sexual harassment, and often times mistreatment.

We believe that service workers across the United States should be paid a fair living wage, by their employer. As an advocate of capitalism and free markets, our belief is that change can only be enacted when current and traditional market forces are disrupted. By forgoing traditional monetary tipping, we believe that we can upset the current status quo, and as a result, service industry workers will feel compelled to demand higher wages that are non-dependent upon monetary tips or subsidies. In our humble opinion, this is the win win for all parties. Patrons will be relieved of the seemingly moral obligation and financial pressures of tipping, and, servers across our great nation will be paid a non-subsidized living wage.

Free Thinking

Have you ever wondered who came up with the percentages to tip? Turns out, nobody knows! In modern day societies, people follow trends and customs out of tradition and the bandwagon effect. Typically, these trends don’t have to have any rhyme or reason behind them. Tipping is no exception. What started out as a European expression of class and wealth, turned into an exploitation of freed slaves, and then morphed into the unfair treatment and exploitation of women and impoverished citizens. If we take a step back and think about why tipping a percentage of our bill makes any sense at all, I think we can almost all agree, it doesn’t. We are all creatures of habit and bandwagon followers. We continue this custom because we believe everyone else is doing it. We don’t actually put much thought into it, which is why a percentage based tip, is so easy to follow and implement. Our perspective is to break free of these social trends and free ourselves from the bandwagon culture that permeates our lives. Free thinking will allow you to make decisions that are rooted in rationale and self interest.

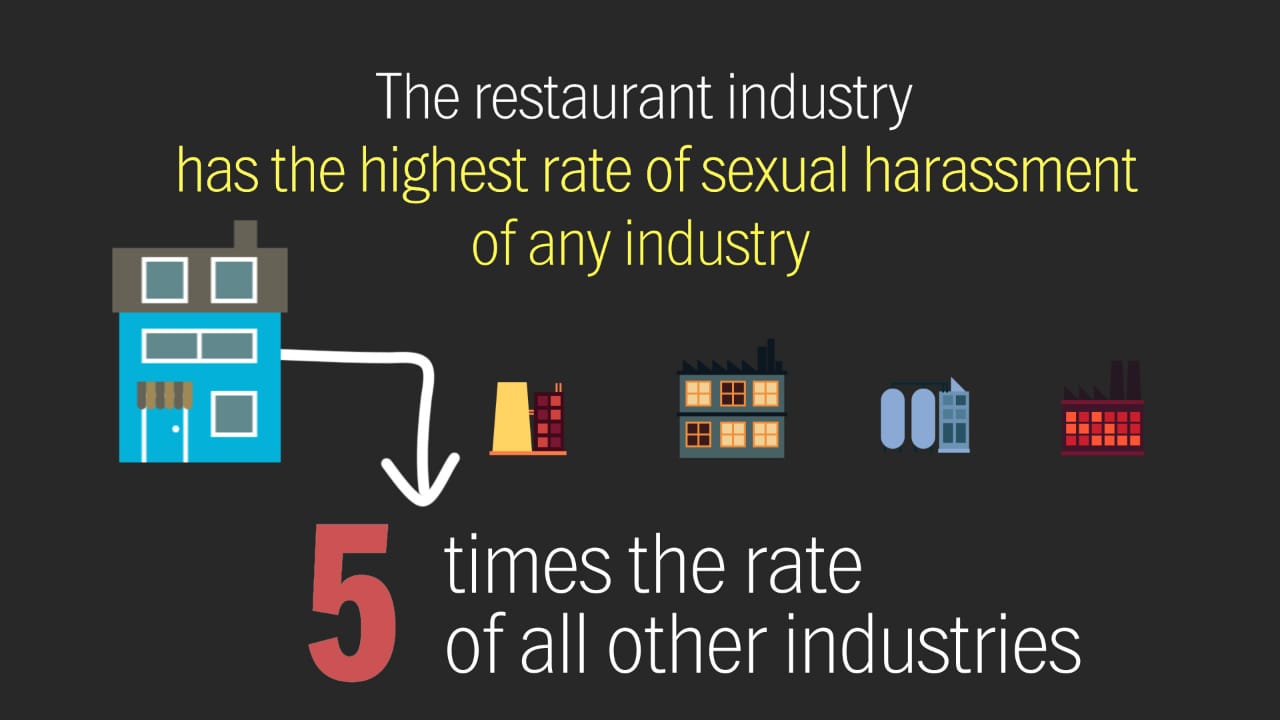

Sexual Harassment & Discrimination

There is broad agreement that the restaurant industry is rife with sexual harassment.

More than 70% of female restaurant employees have been sexually harassed, one recent survey found, and half experience sexual harassment on a weekly basis, according to another. Harassment complaints come to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission from restaurant industry workers more often than from any other sector. Dependence on tipped wages, along with job requirements to appear friendly and pleasant — in other words “service with a smile" — jointly create a culture of sexual harassment, according to a team of researchers at the University of Notre Dame, Penn State University and the Emlyon Business School in France, who say their study is the first to provide an empirical link between tipping and sexual harassment. The results, they said, confirm that dependency on tips and a requirement to appear emotionally pleasant on the job, work together to increase an employee’s risk of being sexually harassed. A 2018 report by the Restaurant Opportunities Center, a nonprofit group that advocates for better working conditions for restaurant workers, found that a majority of respondents who reported experiencing sexual harassment associated that harassment to their dependence on tips.

While women make up roughly half of restaurant employees overall, they are about two-thirds of tipped employees, who report sexual harassment at higher rates than their nontipped colleagues. More than half of women in tipped jobs said depending on tips led them to accept behaviors that made them “nervous or uncomfortable," according to a 2014 survey from the group.

Not only that, tipping is discriminatory. Preliminary research suggests that restaurant customers of both races routinely tip white servers more than black ones. That being the case, today’s tipping practices might actually be illegal under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, researchers claim. That law prohibits employment discrimination based on race, gender, religion, or national origin. The Supreme Court has held that an employer may not have business policies that create the effect of discriminatory treatment, even if those policies appear neutral and were not intended as discriminatory. That means restaurants could be held liable if their tipping policies result in non-white servers–or female, Muslim, homosexual, or immigrant servers–earning less than their colleagues.

Peer Pressure

If you ask most people why they tip, they’ll probably give one of a few common responses; To reward good service, or because it’s the right thing to do. Studies have now shown that the real reasons why we tip are actually pretty arbitrary. A study revealed that more times than not, we tip based on mood, the weather, social queues, touching, or life events, to name a few. Michael Lynn, a professor at Cornell’s School of Hotel Administration and a former waiter at Pizza Hut, says there is another explanation: We tip because we feel guilty about having people wait on us. It’s a way of saying: “Here, have on drink on me when you’re done working."

This is the social pressure theory of tipping, an idea first put forward by anthropologist George Foster.

This theory explains why we tip some people but not others. We tend to tip in places where we’re having a lot more fun than the people who are serving us: bars, restaurants, cruise ships. But we usually don’t tip in grocery stores or dentist’s offices. There’s a subconscious feeling of guilt. Additionally, there’s also the added component of social pressures from our peers. Nobody wants to be that person that stiffs the waiter/waitress for a customary tip. Often, out of a feeling of being chastised or ridiculed by our peers, people will leave a tip even when the service was problematic or not satisfactory. Our peers judge us based on our willingness to tip and the amount we tip. We often feel ashamed when the perception is that we are not good tippers or if we don’t agree to conventional tipping practices.

Fiscal Responsibility

The bureau of labor statistics says the average American spends over $3100 a year eating out. That approximates tipping costs of around $600 or more annually. For most Americans $600 is a significant amount of money that could be helpful in paying down debt, a car payment, utility bills, a family trip, or gas for a week if you live in California! (Just kidding) In this day and age, when fiscal responsibility is being advocated and practiced more and more, it’s understandable if a patron wants to dine on a budget. We don’t know anyone’s financial circumstances at any given time, and so it’s not anyone’s business how much another person decides to tip or not tip. No judgment!

Resources

- https://www.eater.com/a/case-against-tipping

- https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/22/leaving-a-tip-is-an-american-custom-why-thats-a-problem.html

- https://www.thrillist.com/eat/nation/why-you-should-stop-tipping-reasons-not-to-tip

- https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/05/opinion/minimum-wage-racism.html

- https://onefairwage.site/

- https://www.highroadrestaurants.org/

- https://gastropod.com/hot-tips/

- https://thecounter.org/restaurants-unionize-seiu-aoc-warren/

- https://www.npr.org/2021/03/22/980047710/the-land-of-the-fee

- https://www.cnet.com/personal-finance/15-federal-minimum-wage-amendment-fails-in-senate-heres-what-you-should-know/

- https://www.hawley.senate.gov/senator-hawley-announces-blue-collar-bonus-pay-raise-american-workers

- https://www.romney.senate.gov/romney-cotton-plan-would-raise-minimum-wage-protect-jobs-legal-workers/

- https://www.warner.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/1/d/1d8360d5-b403-4355-8d07-4cdfc345cdaf/F303C7C5F63C2C081CE811F205867D8C.raise-the-wage-act-of-2021-fact-sheet-final.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=O_52M3XRs1Q

- https://hyken.com/customer-service-culture/danny-meyers-no-tipping-policy-is-a-lesson-for-any-business-by-shep-hyken/

- https://slate.com/business/2013/07/abolish-tipping-its-bad-for-servers-customers-and-restaurants.html

- https://www.gutenberg.org/files/33170/33170-h/33170-h.htm

- http://www.tippingresearch.com/most_recent_tipping_papers

- https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/26/learning/should-we-end-the-practice-of-tipping.html

- https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/why-do-we-tip

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/02/18/i-dare-you-to-read-this-and-still-feel-ok-about-tipping-in-the-united-states/

- https://www.npr.org/2021/04/01/983314941/throughline-why-tipping-in-the-u-s-took-off-after-the-civil-war

Tipped Minimum Wage States and their rates

Alabama

Georgia

Idaho

Indiana

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Mississippi

New Hampshire

North Carolina

North Dakota

Oklahoma

Pennsylvania

South Carolina

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

Puerto Rico